Week 1

What are the current trends in VFX?

The VFX industry is constantly evolving, with the introduction of new technologies and workflows. The major change happening right now is a move towards “Virtual Production”, this is where the main chunk of VFX work is moved to pre-production, so filming can then be done on “The Volume”. The Volume allows scenes to be shot completely in-camera, whist giving realistic lighting, and something for the actors to react to.

What impact have lenses had on cinematography practices?

Rack Focus

Breaking Bad (2008)

A LIDAR scan of somebody’s room

Dolly Zoom – “vertigo effect”

La Haine (1995)

Jaws (1987)

Bokeh

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Howard Edgerton

Fluid Simulation – X-Men: Days of future past (2014)

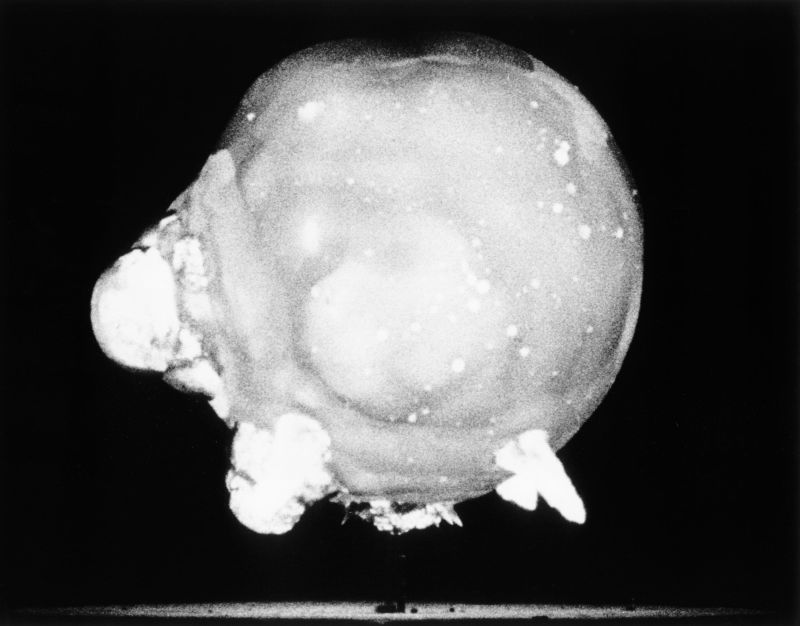

Nuclear Explosion – Oppenheimer (2023)

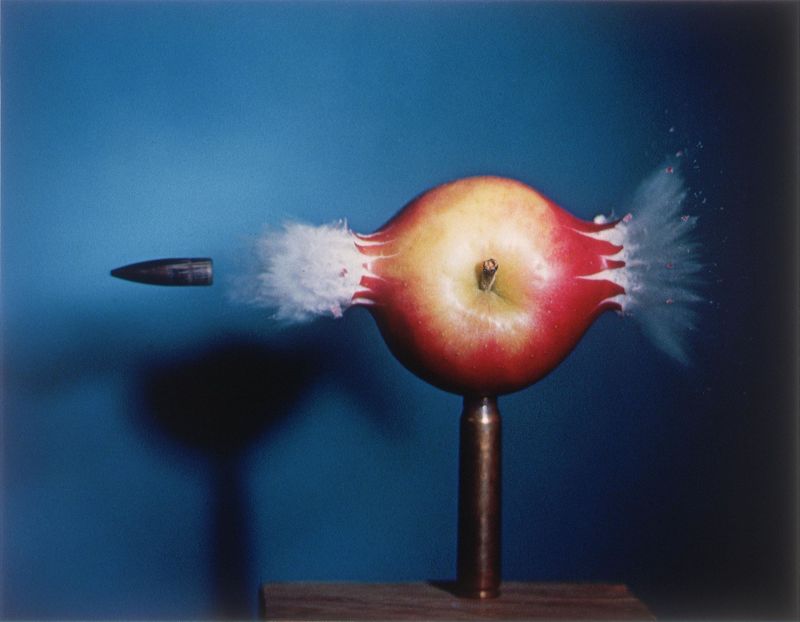

Slow Motion Piercing – RRR (2022)

The Matrix (1999)

Blog Post 1: What is meant by Dr James Fox’s phrase ‘The Age of the Image’?

In episode one (‘A New Reality’, 2020) of his documentary Dr James Fox states that we are living in “The Age of the Image”. This is following the 18th centuries “Age of Philosophy” and the 19ths “Age of the Novel”. He argues that one of the biggest reasons for this is the “democratisation” of image making, starting with the Kodak Brownie camera that allowed the masses to create imagery.

Suddenly photography was no longer just a tool to take stoic images of monarchs, it was for the everyday man to take imagery of his life, in intimate and happy moments. Photography was now needed to make meaning out of these moments. Now in the 21st century this has reached its peak, with the smartphone putting a camera in everyone’s hands. We now take more images every minute, than the entire 19th century combined.

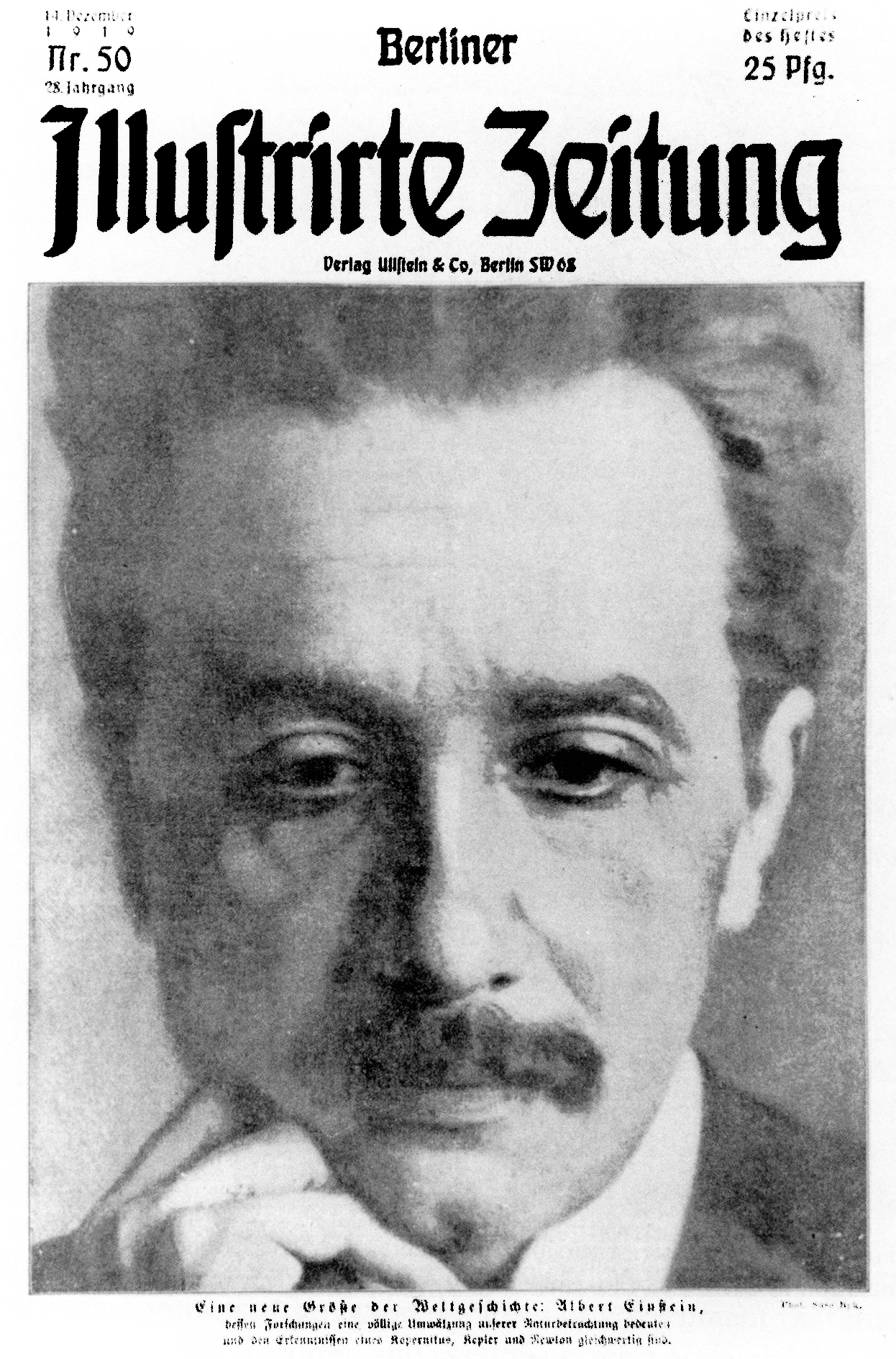

Around the same time as this democratisation of imagery, came the half-tone printing process, this allowed for the printing of images at a much lower cost than before. Now imagery became a commonplace source of information, with newspapers featuring them prominently and frequently. Now imagery could be used to influence the masses on a scale never before seen, so begins the age of the image.

The Kodak Brownie box camera (left), Albert Einstein on the front page of Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 14 December 1919 (right)

Week 2

Plato’s Cave

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-11410491702-07f03ccd0eb54d36a9b62212cd2f55a1.jpg)

Plato’s cave is an allegory for the uneducated gaining knowledge or “enlightenment”. The allegory involves prisoners chained in a dark cave, facing a blank wall. A light is used to cast shadows on the wall, showing different objects. As the prisoners don’t know any different, they take these shadows to be reality, when actually they are just an illusion.

One day a prisoner escapes, the world around him is overwhelming but finally he sees the world as it truly is. The Prisoner then might venture back into the cave to tell his friends, but now the prisoner had become acclimatised to the outside world, he finally sees the cave as it truly is.

The Allegory of the Cave in VFX

The Allegory of the Cave is a popular narrative that is used in films like The Matrix (1999) and Inception (2011). The idea of showing a character a “new” or “true” world is used in both these films.

The Allegory of the Cave can also refer to the use of VFX to “fool” the viewer, like the shadows on the wall fooled the prisoners.

Semiotics – Index and Icon

Blog Post 2: Photographic Truth-Claim

Tom Gunning’s “photographic truth-claim” (2017) refers to the belief that traditional photographs accurately depict reality, which is based on both indexicality and iconicity (visual accuracy) of photographs.

A “truth-claim” is something that is put upon a photo, it’s the claim that what the photo is showing, is true, that what is displayed on the photograph happened in front of the lens. In his paper Gunning refers to the first example of a “photographic truth-claim” in The Octoroon, an 1859 melodrama by Dion Boucicualt. In this play a photograph is discovered that proves that a character didn’t commit a murder, the photograph is making a truth-claim.

Gunning goes on to claim that “a photograph can only tell the truth if it is also capable of telling a lie. In other words, the truth claim is always a claim and lurking behind it is a suspicion of fakery, even if the default mode is belief.” In effect this Truth-Claim can be altered to whatever the user may want to make others believe. In visual effects we are making a “truth-claim” when we create a virtual object that we want the viewer to perceive as real, if the effect is good enough, the viewer will believe that claim.

Week 3 – Faking Photographs

Despite what many think, the act of faking photographs has been around since the emergence of photography itself. Most of these were simple composites of multiple real images to make a single “fake” image.

A composite of multiple images to capture detail that the camera couldn’t do in a single exposure, Carleton E. Watkins, 1867.

Modern Fakes

Fakes are now becoming a bigger and bigger problem in our society due to the emergence of AI programs like DALL-E and Midjourney making it extremely easy to generate convincing images.

This image of Pope Francis wearing a Balenciaga puffer jacket was one of the first AI generated images to widely fool people on the internet.

Blog Post 3: What is VFX Compositing?

Compositing is at the core of the VFX process. The act of compositing is essentially to combine live action footage, with VFX plates and CGI elements, to make them appear that they are part of the same scene. This is one of the final steps in a shots pipeline and has a huge effect on how believable a shot will be to the audience.

The compositing process has been part of movie making since the beginning in the late 19th century, specifically with Georges Méliès and his use of double exposures to combine multiple different plates into one shot, as seen in his short film The Four Troublesome Heads (1898).

During the compositing process you are trying to create an “impression of reality” by making the CGI elements appear as if they were shot in camera with the live action footage. This is done through trying to replicate the effects of the lens on the CGI image, and by colour matching the CG elements to the footage. The process of replicating the lens includes matching the focal length, aperture and position of the camera used for the live action plate in the rendering of the CGI element.

Week 4 – Photorealism in VFX

Blog Post 4: Photorealism

Photorealism in VFX is not the act of making something that is “real” but the act of making something that appears as it would appear if captured through a camera-lens. A viewer’s immersion isn’t broken when what is happening on the screen isn’t possible in real life, it’s broken when what is happening doesn’t look like what it would if it were to be captured by a camera.

This is what is argued by Lister, M et al. (2008, p. 137) in ‘New Media: a critical introduction’:

Thus photography here functions not as some kind of mechanically neutral verisimilitude but as a mode of representation that creates a ‘reality effect’; that is to say, the onscreen event is accepted because it conforms to prevailing or emergent realist notions of screen spectacle and fantasy, not the ‘real world’.

To make something photoreal you must replicate all the effects of a camera lens, like aperture, focal length, and noise (whether digital or analogue). You may also want to think about how your camera acts in physical space, an impossible camera-move can remind the audience that what they’re watching isn’t real. In his presentation ‘The Photorealism Mindset: What About The Physical Camera?’ (Blender, 2023) Asbjørn Lote demonstrated this phenomenon by showing a 3D scene presented in 3 different ways, despite the scene itself being identical, the shots that replicated a real camera felt much more ‘real’ than the first.

Week 5 – Trends of capture

Capturing data is a core part of VFX, from the filming of the actors themselves, to capturing objects in 3D using photogrammetry.

Motion Capture

![]()

Motion Capture is the act of capturing movement using multiple cameras to pinpoint the position of points on an actor’s body and face.

Indexical but not necessarily iconic.

Motion capture is in effect a successor to Rotoscoping, which was used by animators to capture the movement of a live-action actor. Animators often found that if they followed the movement of the actor too closely then the animation would “lose the illusion of life”.

Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is the process of converting a real life object into a 3D model through the use of multiple photos. This creates a 1:1 digital replica of the object.

Blog Post 5: Comparison of Motion Capture and Keyframe animation

In VFX there are two main ways of capturing an animated performance, Motion Capture, and Keyframe animation. The main strength of motion capture is of course its accuracy to real life, it is an indexical record of an actor’s performance, which is then applied to a 3D model, representing this indexical recording. This intertwined indexicality is argued for by Allison, T. (2011):

The character of Kong stands as both an instantiation of the indexical that takes the form of animation (Serkis’ recorded movement animates Kong) and an instantiation of animation that takes the form of the indexical (a digitally constructed creature that literally takes the shape of Serkis’ body in motion).

This helps sell the audience on the reality of the character they are seeing animated, it moves like a real person, therefore it must be real. Directors like James Cameron use this to great effect, the performance of his actors helps sell the fantastical world of Avatar (2009) in a way that keyframe animation could not. However, motion captures strength is also its weakness, realistic movement applied to a non-photoreal world can create an “uncanny valley” effect. Zemeckis’ The Polar Express (2004) is famous for having suffered this problem.

Keyframe animation allows for complete control over every movement a character makes, allowing animators to exaggerate reality instead of replicating it. Whilst animators still use reference footage to help create their animations, they don’t have to stick to it, in-fact sticking to it too closely recreates the same issues as motion capture, it loses ‘the illusion of life’ as noted by Thomas and Johnston (1981 p. 323).

Week 6 – Reality Capture (LIDAR)

This week we took a look at LIDAR scanning as a method to capture the real world. LiDAR allows you to quickly and accurately gather information about your surroundings, which can then be used in combination with photography to create a highly detailed 3D model.

A LIDAR scan of somebody’s room

A Professional LIDAR scanner

Many modern smartphones now have a LIDAR scanner built in, allowing anybody to accurately capture the world around them.

Blog Post 6: Reality Capture Case-Study

LIDAR Lounge are a 3D scanning company, founded in 2014, that use LIDAR and photogrammetry to capture the world for work on TV, Movies and more. 3D scanning has many applications in the film production process, from scanning objects to be used in VFX scenes, to scanning whole sets to give more information to the VFX artists when constructing shots.

LIDAR Lounge have worked on many projects, from scanning items in the British Museum in order to preserve history, to film sets for movies like Mary Poppins Returns and James Bond: No Time to Die. In an interview with UWL VFX Channel (2020) Co-Directors Tamara Mitchell and Ross Clark, they spoke of their work on Mary Poppins. For the movie they had to scan over 300 different props, for example the umbrella, which was both black and shiny making it incredibly hard to scan. They also had to scan an upside-down set, this meant in order to get a good scan they had to get up on ladders, as everything was stuck to the ceiling.

The process of scanning is becoming increasingly Important in the modern VFX industry, as it can be a shortcut to photorealism, especially for more complex objects, that are difficult to model by hand.

Blog Posts: Bibliography

'A New Reality' (2020) The Age of the Image, series 1, episode 1. BBC Four Television. 2 March, 21:00 Gunning, T. (2017) PLENARY SESSION II. Digital Aestethics. What’s the Point of an Index? or, Faking Photographs. Nordicom Review, Vol.25 (Issue 1-2), pp. 39-49. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0268 The Four Troublesome Heads (1898) Directed by G. Méliès. [Short Film] Paris, France: Star-Film. Lister, M. et al. (2008) New Media: A Critical Introduction. 2nd Edition. London: Routledge. Blender (2023) The Photorealism Mindset: What About The Physical Camera?. 23 October. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYlb0-bDZjU (Accessed: 19 November 2023). Allison, T. (2011) 'More than a Man in a Monkey Suit: Andy Serkis, Motion Capture, and Digital Realism', Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Iss p. 325–341. Avatar (2009) Directed by J. Cameron [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: 20th Century Fox. The Polar Express (2004) Directed by R. Zemeckis [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures. Johnson, O. and Thomas, F. (1981) The Illusion of Life. New York: Disney Editions. UWL VFX Channel (2020) The Industry Interviews: Tamara Mitchell & Ross Clark, Co-Directors of Lidar Lounge. 27 February. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSem3o2UXhE (Accessed: 19 November 2023).

Week 7 – Reality Capture (Photogrammetry)

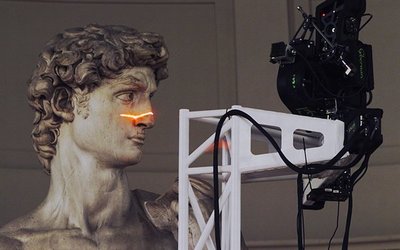

THE DIGITAL MICHELANGELO PROJECT

Photogrammetry was used to create a digital copy of the statues of Michelangelo. With this method the statue could be scanned without any risk of damage.

Assignment 2

For Assignment 2 I chose question 3: “What are Spectacular, Invisible and Seamless effects?”, I will be combining this with the sub-title “Invisible Effects and the rise of the ‘CGI-Free’ movie”.

I want to research how the development of Invisible effects has affected how films are marketed, as many films recently have boasted having “no CGI” whilst having 1000s of VFX shots.

For my research I studied both marketing materials pushed out by movie studios and interviews with actors and VFX artists that worked on these movies.

Assignment 2: What are Spectacular, Invisible, and Seamless Effects? Invisible Effects and the rise of the “CGI-Free” movie

“Did you know they did this for real?” is a phrase you might hear often whilst watching a new blockbuster movie with a friend. In fact, an increasing number of Hollywood movies are marketing themselves on, or gaining traction in the media for, “not using CGI.” However, come the closing credits you’ll notice hundreds, if not thousands of names under the VFX category. In this essay, I will be explaining the difference between “Spectacular” and “Invisible” effects, how the use of the latter has changed the way the world sees visual effects, and how that has led to many movies being deceivingly labelled as “CGI-Free.” To prove this, I will be reviewing studios’ marketing materials and how those compare to the VFX reels that eventually come out after a movie’s release.

When talking about visual effects, they usually fall into one of two categories, Spectacular Effects, or Invisible effects. Spectacular effects are exactly that, spectacular, they are bold and eye-catching and are intended to draw attention to themselves to impress the viewer. An invisible effect’s purpose is to seamlessly integrate with the live-action footage and make modifications that will increase the viewer’s immersion in a scene, whilst not being noticed.

In the early days of computer-generated imagery, VFX was often used to wow the audience, to show them something they never thought possible on camera. This was the age of “Spectacular Effects,” where directors had no shame in shouting about the new things that were possible with computer imagery. This can be seen in movies like James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989), whose main antagonist is the fully CGI body of water, that can replicate the faces of the ship’s crew. These effects were obvious to the viewer as not being “real” but that didn’t matter, as the main attraction was the technology that made these effects possible. The effects then became a main driver in the marketing of a film. This can be seen in movies like Steven Lisberger’s Tron (1982) with the tagline “A world inside the computer where man has never been. Never before now,” a direct reference to how the movie was pushing the boundaries of new computer technologies. Speaking of the ubiquity of spectacular effects in the 2000s, journalist Bryan Curtis said in 2016 “A director trying to get bodies in the seats would tout his big, bold, computer-generated canvas. See: ‘Titanic,’ ‘The Matrix,’ ‘Star Wars: Episode I,’ ‘Transformers’ …, up through the opening salvos from Marvel and D.C. brain trusts.” As a director, James Cameron was at the forefront of pushing these effects in movies, with each movie being a bigger CGI spectacle than the last. This all culminated in his movie Avatar (2009), an almost fully CG movie filmed using motion capture technology, whose huge success can be attributed to its “Spectacular” effects.

As improvements in technology greatly increased the fidelity of the effects we see in movies, so began the rise of the “Invisible Effect.” These types of effects can be seen as far back as the 90s with movies like Forrest Gump (1994), the crowd shot at the Washington Memorial was filmed with just 700 people, made to look like 250,000 by moving them around the scene and repeating the shot with a motion-controlled camera (Forrest Gump – Behind the Scenes, 1994). These effects often go unnoticed by the viewer but can help greatly increase their immersion in a scene by bringing it closer to what the filmmaker envisaged when writing the film. In a 2017 article professor Gabriel F. Giralt states that “realistic visual effects (invisible VFX) imitating ‘likeness’ can substitute entirely for the ‘realism’ of the photographic image. Visually, the effect presents itself as the result of the artist’s genuine encounter with reality, and therefore the digital effect instigates the viewer to accept the popular belief that seeing is believing.” The invisible effect now goes hand in hand with the camera as a means to capture reality, and for the audience, it is completely impossible to determine which is which.

At the turn of the century and into the 2010s the popularity of Spectacular effects in movies was at its peak with huge franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe featuring 1000s of VFX shots in every movie. However, with the huge popularity of these movies also came what many in the industry call “CGI Fatigue.” With each new Hollywood blockbuster, the unashamed use of Spectacular Effects got bigger and bigger, from alien space battles that destroyed New York in The Avengers (2012) to hordes of CGI orcs in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012). Audiences were fatigued, and now looking for an escape, a return to “true” filmmaking. Filmmakers had begun to recognise this and would now pivot to marketing their movies on their use of practical effects rather than CGI, “here was Colin Trevorrow, in 2014—when interrogated about what he’d done to the iconic ‘Jurassic Park’ gate—taking to Twitter to reply, ‘The gate will be practical. Real wood, concrete and steel’” (Curtis, 2016). While in the 2000s directors would be embarrassed to shout about how their film used 80s techniques like prosthetics or miniatures, in the 2010s it was all they wanted to talk about, “what was once cliché becomes an homage to a distant and more cultured time” (Curtis, 2016).

Throughout the 2010s and into the 20s CGI was talked about with disdain both by filmmakers and the media, the less a movie had the more “authentic” and “true” it was. “We’ve gotta do all the Jets practical, no CGI in the jets” Tom Cruise cries in an interview (2015) when asked about the then hypothetical Top Gun sequel. And come the release of Top Gun: Maverick (2022) he would seem to get his wish, if you’re to believe the promotional material for the movie. “No CGI here.” exclaims a tweet from the film’s production company Skydance (2020). This is a confirmation to the audience that there must be no CGI in this movie. Before you know it, IGN articles are written praising the film’s “unprecedented practical effects” (Cardy, 2022), 100s of comments are left on social media stating how happy they are that the movie isn’t using CGI, and so a myth is born. It only takes waiting until the end credits of the film to see the names of hundreds of VFX artists scroll by who together worked on the film’s 2,400 VFX shots (fxguide, 2023). Whilst they did film most of the jets practically, almost every one of them was a stand-in jet that had to be replaced with a CGI double, as the F-14 jets from the original Top Gun were no longer available. These jets were painted grey and plastered in tracking markers, allowing for seamless replacement in post-production. “They acted as sort of an aerial motion capture for us,” explained VFX Supervisor Ryan Tudhope in an interview with fxguide (2023).

All this isn’t to say that doing it practically isn’t needed, practical footage whether of fighter jets or race cars is incredibly useful for the VFX artists in post-production, providing perfect reference footage. Shooting in a real situation also helps the actors give a much better performance, even if it does end up being ultimately replaced by CGI. “It’s always a treat for an audience when something feels more real. Shooting this movie without green screens, without projectors, I think gives the more honest performance” says Actor Darren Barnet in a featurette about Gran Turismo (Sony Pictures Entertainment, 2023), a movie that much like Maverick, was marketed on its use of practical effects, despite the fact that it had well over 1000 VFX shots (Failes, 2023).

In recent years this “No CGI” mythmaking has been incredibly common, with recent movies like Oppenheimer (2023), Napoleon (2023) and Barbie (2023) all being praised for their apparent lack of CGI (D’Souza, 2023), despite all of them containing it. Often you see this mythmaking coming from the actors themselves. They should know whether a shot they were in had CGI, right? Well, advancements in technology have meant that VFX is not only invisible in the final movie, but also on set. In the 2000s, it was extremely obvious to an actor when they were involved in a VFX shot, the set might be wrapped in green screen to allow for digital set extension, or they might have to act alongside a tennis ball that would be later replaced with a CG character. But as technology has progressed and VFX studios have grown it has become easier for them to manipulate footage without all this on-set prep. The film Mad Max (2015) was full of digital set extensions, yet no green screen was to be seen anywhere on set, everything was painstakingly rotoscoped by VFX artists instead. When talking about the robotic character BB-8 in The Force Awakens (2015) Mark Hamil (2014) said, “When they were demonstrating how they did this thing, live on set — because it’s not CGI, that’s a live prop — I was just amazed.” However, in most of the final shots, BB-8 was actually replaced with a CG double, but there is no way for Hamil to know this as the one he saw on set was fully practical, but these comments still went on to propagate a myth that the character in the movie was completely practical.

With the rapid evolution of technology, the shift from “Spectacular” effects to “Invisible” ones has reshaped how audiences perceive the use of visual effects in cinema. As I explored in this essay, the technological marvel of CGI once dominated Hollywood with directors proudly showcasing how they pushed the boundaries of the new technology in a bid to draw in audiences. These “Spectacular” effects dominated the screen with no shame, with directors like James Cameron pushing the boundaries with each new release. However, as filmmaking behemoths like Marvel pushed out more and more CGI-dominated movies in the 2010s audiences developed so-called “CGI Fatigue”. In response to this came a resurgence of practical effects or, “doing it for real”. Instead of touting their visual effects directors now touted how their movies were made “the old-fashioned way”. But with the evolution of technology came the rise of the “invisible” effect, and the lines between digital and practical became increasingly blurred. This led to studios marketing movies like Top Gun: Maverick (2022) and Gran Turismo (2023) on their apparent absence of CGI, even though they had over 1000 VFX shots each. Despite how they are portrayed in the media, I believe that practical and visual effects are not opposed to each other. It’s the combination of both practical and invisible effects that is necessary for filmmakers to capture authentic performances from their actors, whilst also allowing for things not possible through purely practical means. The use of deceptive marketing from studios on their use of practical effects has only been possible through the massive technological evolution of visual effects, and the hard work of the artists who create them.

Bibliography

The Abyss (1989) Directed by J. Cameron. [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: 20th Century Fox. Tron (1982) Directed by S. Lisberger. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Buena Vista Distribution. Avatar (2009) Directed by J. Cameron. [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: 20th Century Fox. Forrest Gump (1994) Directed by R. Zemeckis. [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: Paramount Pictures. Giralt, G.F. (2017) 'The Interchangeability of VFX and Live Action and Its Implications for Realism', Journal of Film and Video, 69(1), pp. 3-17. https://doi.org/10.5406/jfilmvideo.69.1.0003 Curtis, B. (2016) Hollywood’s Turn Against Digital Effects. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-turn-against-digital-effects (Accessed: 25 01 2024). The Avengers (2012) Directed by J. Whedon. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012) Directed by P. Jackson. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures. Cruise, T. (2015) Will Tom Cruise Reprise Maverick Role in 'Top Gun 2’?. Interviewed by AJ Calloway. extratv. 23 July. Available at: https://youtu.be/C_ez-T2jUPY (Accessed: 27 01 2024). Top Gun: Maverick (2022) Directed by J. Kosinski. [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: Paramount Pictures. Skydance. (2020) 'No CGI here.' [Twitter] 10 June. Available at: https://twitter.com/Skydance/status/1270746344379080705 (Accessed: 25 01 2024). Seymour, M. (2023) Flying Top Gun: Maverick with Ryan Tudhope. Available at: https://www.fxguide.com/fxfeatured/flying-top-gun-maverick-with-ryan-tudhope/ (Accessed: 27 01 2024). Sony Pictures Entertainment (2023) GRAN TURISMO - Neill Blomkamp's Approach. 28 October. Available at: https://youtu.be/mzRZQwR0LEE (Accessed: 27 01 2024). Failes, I. (2023) ‘Make them go F.A.S.T.’. Available at: https://beforesandafters.com/2023/09/16/make-them-go-f-a-s-t/ (Accessed: 27 01 2024). Oppenheimer (2023) Directed by C. Nolan. [Feature film]. Los Angeles, CA: Universal Pictures. Napoleon (2023) Directed by R. Scott. [Feature film]. Cupertino, CA: Apple Original Films. Barbie (2023) Directed by G. Gerwig. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures. D’Souza, S. (2023) ‘It’s exactly as they’d have done it in the 1910s’: how Barbenheimer is leading the anti-CGI backlash. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/jul/27/its-exactly-as-theyd-have-done-it-in-the-1910s-how-barbenheimer-is-leading-the-anti-cgi-backlash (Accessed: 27 01 2024) Hamil, M. (2014). Mark Hamill on Playing With the 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' Ball. Interviewed by Gwynne Watkins. y!entertainment. 12 December. Available at: https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/mark-hamill-on-playing-with-the-star-wars-the-105015597302.html (Accessed: 27 01 2024).