Heathrow: The Journey is a permanent exhibition at UWL’s Ealing campus on St Mary’s Road. Due to the pandemic the campus is currently closed to visitors. In order to ensure the exhibition is still available for all to explore, we have included some highlights from the exhibition here for you to explore virtually…………

Heathrow: The Journey

For over 70 years Heathrow Airport has been at the centre of the air travel revolution.

Today it’s the world’s second-busiest airport, welcoming travellers from 82 countries and serving 194 destinations worldwide.

How did a site that began as a small, grass airfield become one of the globe’s biggest travel hubs? This exhibition displays historical items from the Heathrow Archive revealing how Heathrow evolved………

Heathrow’s life as an airport began by chance. It had been a small, rural hamlet for centuries – but that changed when, in 1925, RAF test pilot Norman MacMillan was forced to make an emergency landing and take-off there. He realised the flat terrain was ideal for an airfield.

Four years later, British aero–engineer Richard Fairey suddenly found himself in need of a new airfield for his aircraft-building business. The Air Ministry had served notice on his aerodrome at Northolt and Fairey needed to find a new venue fast. MacMillan mentioned Heathrow and together they investigated the site’s potential. It was perfect.

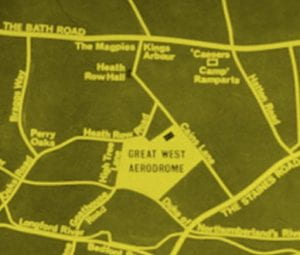

The Great West Aerodrome

£15,000: that was the bargain sum aero-engineer Richard Fairey paid in 1930 for 150 acres of farmland at Heath Row. (Today that’s equivalent to around £874,500.)

On that rural plot Fairey built his new aerodrome – briefly named Harmondsworth, then rebranded more grandly as the Great West Aerodrome.

The private airport’s purpose was primarily for assembling and testing Fairey Aviation’s new aircraft. It was also used by model aircraft enthusiasts, and it hosted the Royal Aeronautical Society’s annual garden party fly-ins. Modest beginnings for a site destined to become one of the world’s busiest international airports.

War and Peace at Heathrow

During World War Two the Air Ministry requisitioned Fairey’s private aerodrome and the surrounding roads, farmland and buildings. Fairey wasn’t thrilled by this and began a legal dispute with the government that lasted 20 years. He finally received £1,600,000 in compensation.

Heathrow’s early passenger terminal, 1946. Also in view are BOAC vehicles, plus a row of houses soon be swallowed up by the expanding airport – Image courtesy of British Airways Heritage Centre

An RAF base was built on the site for long-range bombers and aircraft carrying troops to the Far East. Three runways were constructed along with a control tower – all ready for action by 1945.

Inside the early passenger terminal, with WH Smith newsstand and Western Union cablegram desk, 1940s. The army surplus tent was a short walk from the aircraft, UWLA-HA-01-08-02-003

But suddenly the war was over. A military aerodrome now seemed surplus to requirements. What followed was a decisive moment in the site’s history: Heathrow was made London’s first international civil airport on New Year’s Day, 1946. Some later claimed this was the intention all along.

An Airport for London

Star Light was the first aircraft to use London Airport. It was a British South American Airways (BSAA) Avro Lancastrian – photographed here in May 1946 UWLA/HA/02/02/006)

The new airport was a hive of activity. Concrete runways were built and extended. The makeshift terminal’s tented marquees were soon replaced by prefab buildings. The airport’s footprint was rapidly expanding – and the local landscape would be transformed beyond recognition in the process.

The new port was billed as ‘one of the junctions of the world’. South America, Australia and the USA were among the first destinations to welcome flights from the runways of Heathrow.

But not everyone was happy with London’s new airport. Some local residents were highly resistant to further expansion – there was much public protest at a planned northward extension, which was cancelled in 1953.

London Airport grew rapidly in the 1950s and ‘60s.

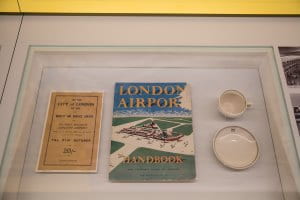

City of London Air Tour from London Airport flyer by Birkett Air Service, 1950s; London Airport Handbook and visitor’s guide, 1957; Ridgeway porcelain cup and saucer for BEA first class passengers, 1955

More airlines set up business there and passenger demand kept rising. New aircraft such as Tridents, VC10s and Boeing 707s began taking greater numbers of people to an increasing number of destinations worldwide.

The era is nostalgically called the ‘golden age of flying’, even though journey times were often far longer and aircraft technology less sophisticated.

Flights were also far more expensive – a return ticket from London to Sydney, Australia, would have cost up to five times as much as today. It may have taken up to four days, with several stop-overs and overnight stays en route. Today the same journey takes around 22 hours with just one stop for refueling.

A New Terminal

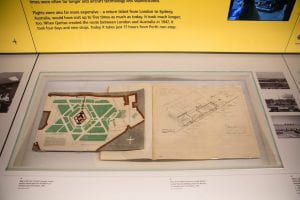

In 1951 architect Frederick Gibberd set to work designing permanent buildings for the airport.

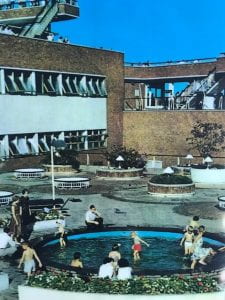

He created a central area reached via a subway underneath the original main runway, plus the Europa passenger terminal, an office block and, at the centre of it all, an impressive 127-foot-tall control tower.

HM The Queen opened the new terminal in 1955 – in the years ahead she’d be back on several occasions to perform similar duties.

By the early ‘60s the old terminal on the north side was redundant. Airlines either operated from the Europa terminal or the Oceanic terminal (later renamed the slightly less evocative Terminals 2 and 3).

New Horizons

Air travel was still beyond the reach of many working class people in the ‘50s. Many saw it as an impossibly glamorous experience, for the rich and famous only.

But by the late ‘60s this view was changing fast. Package holidays were beginning to make foreign travel affordable for the masses. Advertising sold the idea of flight as a luxury and a pleasure that placed exotic destinations within reach. International tourism was booming and – for better and worse – began reshaping the landscape and economies of destinations such as the Mediterranean.

Demand for flights continued to grow and grow. By 1969, when Terminal 1 opened and Concorde took its maiden flight, Heathrow was hosting five million passengers a year. The modern age had arrived.

The Glamour of flight

Famous passengers have been part of the Heathrow story from the beginning. But as pop culture transformed western society in the ‘50s and ‘60s, celebrity and international travel became truly synonymous.

The arrivals and departures of royalty, dignitaries and icons of sport, stage and screen regularly made the news headlines. Fans began turning up in crowds to catch a glimpse of their heroes or maybe get an autograph.

By association, the great and the good helped to sell the dream of air travel to the masses– it was said that ‘everybody that’s anybody flies out of Heathrow’.

Advances in aircraft technology changed air travel dramatically from the ‘70s onwards. Bigger, more powerful new jet planes such as Boeing 747s and supersonic Concorde transported more people further and faster than ever before.

Journey times shrank and access to even more destinations made the world a smaller place. But Heathrow just kept on growing – ever-increasing demand meant more planes, more staff and more facilities were needed.

Although other regional UK airports such as Manchester, Birmingham, London City and Stansted expanded markedly during this period, it didn’t seem to dent Heathrow’s business. In fact passenger numbers rose there by around 13 million between 1993 and 1998 alone. Heathrow had twice as many passengers as Gatwick, too: its status as the UK’s leading international hub was unassailable.

Concorde: rise and fall of a legend

Concorde’s first scheduled UK flight in 1976 was a watershed moment in aviation history. Overnight the supersonic plane became a powerful symbol of modern progress, national pride and international cooperation.

Conceived as a joint Anglo-French initiative, the fleet of 20 supersonic airliners were exclusive to British Airways and Air France. Used by royalty, heads of state and celebrities, Concorde swiftly captured public imagination.

Despite its success, the iconic plane’s days were numbered. Commercial flights ceased in 2003, three years after the Air France Paris runway tragedy that killed 113 people.

Yet Concorde refuses to fade into history. It remains a design classic, regarded with affection by many. There are even plans to revive one aircraft for active service by 2019.

HRH Prince Charles and Princess Diana arrive at Heathrow for the inauguration of Terminal 4th May 1986, UWLA-HA-01-08-02-020

Good connections

Heathrow’s growth accelerated during this period. Terminal 4, officially opened by HRH Prince Charles and Princess Diana in 1986, reflected the need to expand the airport in order to cope with rising demand.

Improvements to infrastructure were also crucial for keeping pace.

Tom Eckersley ‘Concorde’ mural which was one of nine displayed on the terminal of Heathrow Central underground station when it opened in 1977.

Getting to Heathrow was made easier when the London Underground rail link opened in 1977. The M25 motorway also improved access by car (at least on days without road works and traffic jams).

Clay extracted from 25 metres below the northern runway during the construction of the Heathrow Express tunnels which were completed in 1998.

From 1998, the Heathrow Express service also began offering speedier connections to and from the airport – at a price.

At the end of the ‘70s, over 27 million passengers were using Heathrow annually. By 1990, this has climbed to 40 million and still rising.

Heathrow at 50

In 1996 Heathrow Airport celebrated its 50th birthday. The party was attended by HM The Queen who, accompanied by HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, also officially opened a £32-million refurbishment of the Terminal 2 departure lounge.

The milestone celebration included a recreation of the original 1940s tented departure lounge, complete with wicker chairs and staff in period dress.

Nearby, anti-noise pollution protesters staged their own alternative garden party. After half a century Heathrow still had its critics, and plans for Terminal 5 were met with a distinct lack of enthusiasm by some. The T5 planning inquiry became the longest in British legal history, taking eight years and generating 100,000 pages of transcripts from 700 witnesses. The Terminal finally opened in 2008, at a cost of £4.3 billion.

Now in its eighth decade, Heathrow Airport has come a long way from its humble beginnings as a grassy airfield surrounded by country lanes.

The airport’s story has been a remarkable continuum of growth that reflects the changing world around us.

London’s first airport continues to evolve as it looks to the future. As ever, rising demand remains a challenge, but now on an immense scale that would have been unthinkable in the early years.

Air travel and airports too, are changing, as the tech revolution transforms all aspects of our lives.

T2: Good-bye and Hello

By the turn of the millennium Heathrow’s original Terminal 2 was showing signs of its age. Upgraded facilities were needed to keep pace with modern demand.

In 2008 the airport began construction on a state-of-the-art new Terminal 2, also known as the Queen’s Terminal. The original building was demolished in 2010 and the new Terminal 2 opened for business on 4 June 2014. It includes a new five-storey main building and, running parallel, T2B – a satellite pier.

Olympian heights

In 2012 Heathrow welcomed thousands of athletes, officials and spectators for the London Olympic and Paralympic Games.

To cope with this additional surge in passenger numbers a temporary terminal was built – diverting more than 10,000 athletes (and 37,000 bags) away from the other terminals during the busy peak summer period. Additional lifts were also built to accommodate Paralympians’ wheelchairs, and extra spaces were created for volunteers and the media.

Four years later, in 2016, Heathrow welcomed many of Team GB’s athletes back from the Rio Olympics on BA flight BA2016. Also onboard: 92 medals, weighing a total of 46 kg!

The Future of Heathrow

Artist’s impression of what a proposed third runway might look like. Image courtesy of LHR Airports Ltd

Pressure for expansion at Heathrow has never been greater. Passenger numbers are at an all-time high and demand for international travel is predicted to continue rising. The airport currently runs at close to 100% capacity. Expansion at Heathrow would create up to 180,000 jobs and around £187 billion in economic benefits across the country.

Aircraft: the next generation

Could Heathrow be hosting some of these exciting new aircraft within a few years? Image courtesy of NASA

Supersonic flight was developed over 70 years ago, but since the axing of the Concorde fleet it has slipped off the public radar.

Advances in aerodynamic engineering and tech efficiencies are set to change this. New jets called Boom airliners are now in production and can achieve a speed of Mach 2 (that’s 1,451 mph – faster than Concorde). This has the potential to cut journey time on many long-haul flights by half.

Virgin and Japan Airlines have already ordered quantities of these new jets and promise fares equivalent to current Business Class tickets.

But that’s not all. NASA and partners are also developing a radical new type of passenger airliner. Called the Blended Wing Body (BWB), it has the potential to carry more passengers and cargo yet is more aerodynamic and fuel-efficient than conventional planes.

Pilotless planes

Autonomous vehicles are becoming a reality on our roads, and it could be a similar story in the skies. The first pilotless passenger aircraft may be in service by 2025.

Auto-pilot controls and automated landings are nothing new, but computer system-supported flight – called ‘fly by wire’ – has radically changed how aircraft are piloted in recent years. Fully automated cockpits may be the next step and some argue that it will save the industry – and passengers – billions.

But the concept is a controversial one. Pilots and airline staff are concerned about costs, jobs and safety. The risk of computer hackers taking control of an automated cockpit could be a serious threat if systems are not airtight. And passengers seem to agree: a recent survey found that 54% of 8,000 people questioned would refuse to travel in a pilotless plane.

While public opinion may change in future, it seems more likely that our international flights will include a real, live pilot for the time being.

Greener air travel

Aviation currently contributes around 2% of global CO2 emissions. With passenger numbers worldwide predicted to rise to 7.2 billion annually by 2035, the number of flights will increase. Carbon emissions from aviation may rise by around 300% by 2050 unless the industry invests in more eco-friendly tech. And that is exactly what’s happening.

Today’s flights emit half as much pollution as they did in 1990, but modern aerospace design and engineering continues to improve on this. Aircraft are becoming more streamlined and aerodynamically efficient. Use of carbon-fibre and other weight-saving materials is reducing fuel consumption, along with design innovations such as winglets that reduce drag. A new generation of jet engines also allows more efficient use of fuel.

And fuel is changing, too. Alternatives such as hybrid-electric power and biofuels will add less CO2 to the air than fossil fuels – and hydrogen powered aircraft have the potential to be a zero emissions solution. Jet emissions could be reduced by up to 70% by mid-century.

Sky’s the limit

As the number of international flights continues to rise, maximum capacity in the skies is fast becoming a reality. So what can be done to improve and maintain the global air travel network when this happens?

Air traffic controllers’ view of Heathrow. What might the control tower of the future look like? Image courtesy of LHR Airports Ltd.

A multi-solution approach is needed. Smarter systems of air traffic control are being developed and implemented, increasing efficiencies in time management for arrivals and departures, and costs to airlines. Control towers may become a thing of the past – London City Airport has already adopted a digital system where cameras relay images to a remote control room. Sophisticated computer systems could also allow more aircraft in the air at the same time, creating motorways in the skies.

Onboard, flexible navigation systems are already replacing some preset flight paths. These enable aircraft to avoid weather conditions that cause delays and add to fuel consumption. A single flight using flexible navigation may save 1.4 tonnes of CO2.

In modern aviation, data is now key to improving services… but where will it take us in the coming decades?

You are your ticket

Biometric passports and automated ticketing are already here, but could be set to evolve further in the near future. Facial or palm recognition technology at check-in and boarding could see physical tickets and boarding passes become a thing of the past.

Mobile tech may also provide passengers with wayfinding, flight information and constant Wi-Fi connectivity door-to-door – in theory, a more seamless travel experience.

Automation will likely spell the end of traditional departure halls. Check-in desks may vanish, and baggage sorting, customs and immigration may be streamlined.

And, as traveller processing functions become more efficient using less space, so more of that space may be devoted to passenger experience airside after check-in.

Destination: Heathrow

What will the Heathrow Airport of the future be like?

One change we can expect is the transformation of the airport itself as a leisure destination. State-of-the-art facilities for visitors will make the airport more than just a place of transition.

Other international airports such as Singapore’s Changi and Dubai International in the UAE have already established a look and feel for 21st-century airports that moves beyond traditional, uniform and functional design. Instead they provide more state-of-the-art facilities and a greater sense of place. This approach is set to spread globally as we spend more time in airports and the nature of what constitutes an airport evolves with technological advance and consumer demand.

One day you may visit Heathrow for just a shopping trip or a meal. Maybe you’ll go to a cinema, visit a garden or workout at a gym. And for once, forgetting your passport won’t be a disaster.

“Heathrow: The Journey” was made possible by generous funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, Heathrow Airport and the University of West London.

With special thanks to:

British Airways Speedbird Heritage Centre

London Transport Museum

Curator & writer: Steven Swaby

Archivist: Anne-Marie Purcell

Graphic design & creative direction: Andy Spencer Design Ltd

3D design: One&More Ltd

AV: Kristina Stafecka/W5 Productions

Project management: Laura Thomas Ruth Cribb

For more information about the Heathrow exhibition see our webpage: https://www.uwl.ac.uk/study/hospitality-tourism/heathrow-exhibition

Also see UWL archives for more information about historical collections held by UWL: https://www.uwl.ac.uk/library/library-services/university-west-london-archive

To search the archive, see the UWL Archive catalogue: https://archives.uwl.ac.uk/index.php/