Our ‘Layers of London’ volunteer has compiled an interesting history of the University of West London. Alison Homewood looks into the fascinating history of UWL and its predecessor institutions:

Anyone who knows UWL, whether student, lecturer or Ealing resident, would be forgiven in thinking that the establishment – which is known as “The Career University” – is relatively new.

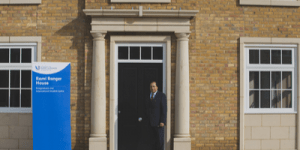

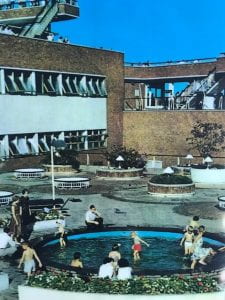

UWL’s ‘The Park’ entrance on UWL’s Ealing Campus

The striking building is modern, the curriculum and student body diverse and dynamic, and its reputation is on the up; it is ranked in the top 60 universities in the UK by The Guardian University Guide 2020 and TheTimes/Sunday Times Good University Guide 2020. UWL is the ‘Top university in England for student satisfaction’ – NSS 2020 – average of all questions. The roots of UWL reach back to 1860, making it older than universities such as Warwick (1965), Imperial College (1907) and Leeds (1874) with a unique history that should be a source of pride.

Part One: The Early Years 1860 – 1913

A blue plaque on the front of UWL’s main building on South Ealing Road commemorates Lady Noel Byron’s Co-operative School, based on this site between 1834-1859. Lady Byron, wife of the famous poet, lived in Ealing at Fordhook House, opposite Ealing Common Station.  She was a keen social reformer whose “industrial school” was the first of its kind in the country. It offered an education for fifty boarders and thirty day-boys “from the common ranks”. They learnt English, Grammar, History, Geography and Geometry, as well as carpentry. They also worked in the school garden three hours a day. At the time, the school was based in the former stable block and coachman’s house of Ealing Grove House, a large mansion demolished in 1850. The Byron School became Ealing Grammar and stayed open until 1917.

She was a keen social reformer whose “industrial school” was the first of its kind in the country. It offered an education for fifty boarders and thirty day-boys “from the common ranks”. They learnt English, Grammar, History, Geography and Geometry, as well as carpentry. They also worked in the school garden three hours a day. At the time, the school was based in the former stable block and coachman’s house of Ealing Grove House, a large mansion demolished in 1850. The Byron School became Ealing Grammar and stayed open until 1917.

From 1860-1886, an art school took place in Christ Church School. It was put on a more formal footing when a headmaster, Mr T.W Cole, was appointed. He found new premises in the basement and then the top floor of the newly built Town Hall. In 1913, the school moved to the top floor of Ealing County School which had just been built near Pitzhanger Manor on Ealing Green.

In 1913, the school moved to the top floor of Ealing County School which had just been built near Pitzhanger Manor on Ealing Green.

From 1892, a Technical Institute had been based in two houses and stables on Uxbridge Road. By 1905, it had moved into a house on Ealing Green (right).  This was demolished to make way for the County School, and in 1913, the Institute also moved onto the top floor of the new school.

This was demolished to make way for the County School, and in 1913, the Institute also moved onto the top floor of the new school.

Part Two: The Expansion Years 1924-39

Barker’s Studios

In the early 1920s, the Art School and the Technical Institute had completely outgrown their squatted premises. By 1925, the Art School alone had 320 pupils, 54 of which were full-time. When Will Barker’s Film Studios came on the market, a deputation from the two establishments argued that the Council should buy it, saying “the facilities for technical and art education in the Borough were totally unacceptable.” Instead, however, the Council compulsorily purchased land in The Park, adjoining the new Ealing County School for Girls. The acquisition nearly fell apart at the last minute when the owner decided to inflate the price from the agreed £1,400, but eventually the sale went through and in October 1925, the council had become the owner of “2 roods and 7 poles” of prime Ealing real estate for the new combined facility. Headmaster Mr. Cole had begun this initiative and his successor Charles Trangmar continued it. Trangmar had previously been Head of the Salisbury School of Art and was himself a successful artist who regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy. His consistently enlightened and energetic approach ensured he stayed in the post of Principal until his retirement in 1953.

So finally, on September 18th, 1928, the new Ealing Technical Institute and School of Arts and Crafts opened the doors of its bespoke new building on Warwick Road. The building was designed by H. G. Crothall, the county architect, built by Mssrs Leslie & Co at a cost of £28,00 and equipped with all the latest appliances. It was a three-storey structure, roughly H-shaped in plan. Set in half an acre, it was built in Fletton bricks, faced externally with multi-coloured bricks with stone dressings; a portion of the roof was tiled with sand-faced tiles but the Life, Antique and Modelling and Carving rooms were north-lighted and covered in slating. There were two entrances, two for men (one to the Art School and one to the Technical Institute) and two for women.

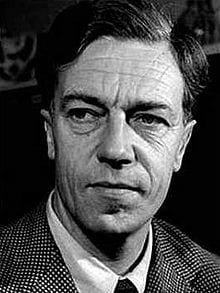

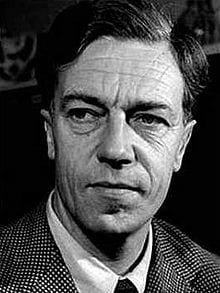

Lord Eustace Percy

Lord Eustace Percy, (right) the President of the Board of Education, hoped it would “help Middlesex and the south of England avoid the industrial revolution mistakes made in the north of the country.” Councillor Fuller, the Chairman of Ealing Higher Education Committee, said that the industrial revolution of the previous century had divorced art from industry, much to the loss of both and while this school did not suggest re-marriage, he felt they were witnessing “the beginnings of an interesting and hopeful flirtation.”

There were two large rooms for women’s crafts, equipped with sewing machines, looms for weaving and apparatus for upholstery. On the main corridor were woodwork and metal-work workshops. The first floor had a printing room, a design studio and a lecture room, with a typewriting classroom in the east wing. The wings of the top floor contained several large studios with top lights and also housed a modelling room, a casting room, a life room and painting room with equipment for photographic finishing. There was a large exhibition space with top lighting and a large elementary art room. A large portrait of Councillor Fuller painted by the Principal Charles Trangmar, was hung in the hall.

But by January 4th, 1930, the new establishment was already proving too small and some evening classes had to be taken in the neighbouring County School for Girls. Enrolments in the Technical Institute had grown to 1,043. There were three main departments; Commerce, Matriculation and Modern Languages, as well as a course for Building Construction, and classes in Cookery and Physical Training for women.

The School of Art had also increased in numbers to the point where it had to duplicate some of the classes. It trained

Slade School

students for careers in Commercial Art through classes in fashion drawing and, lettering and drawing for process reproduction and graphic art. Many students also went on to further study at the Slade School or Royal College of Art.

It now ranked as the second largest school in the county. Its popularity was due to the combination of up-to-date facilities, modern organisation, close ties with industry, a high standard of teaching and a curriculum designed to meet the needs of trades devoted to the commercial use of draughtsmanship and design. It also offered an extensive range of arts and handicrafts classes for those who did not necessarily follow art professionally.

Sanderson’s Wallpaper Factory

By 1931, the Art School had become the largest art school in Middlesex, with 654 students, up from 317 when it transferred to the new building in 1929. Several of the EAS students had joined Messrs. Sanderson’s wallpaper company in Perivale, and the Aladdin Lamps factory in Greenford.

Plans were submitted in July 1931 for a new block of buildings to be erected on the Warwick Road frontage, with accommodation for craft rooms and caretaker’s quarters but these were deferred due to instructions by the Board of Education.

Yet in 1934, there were 2,018 students enrolled across the two establishments. Courses now included Drapery and Outfitters, Silversmithing, and Salesmanship in Retail Distribution. United Dairies Ltd had become another local business offering employment to graduates of the College. One student, 20-year-old Edward Pearson, even built a full-sized motor boat during his evening woodwork classes.

Cecil Day-Lewis

In 1936, Middlesex County Council approved the purchase of the vacant St Mary’s Church House at 91 Warwick Road, and three-quarters of the land adjoining Ealing Vicarage to enable the Institute to be enlarged. The price agreed was £7,820 and it added 580ft of frontage on Warwick Road and 175ft on The Park side. The author Cecil Day-Lewis (left) had lived in Church House as a child in 1908.

Music became a new focus in 1936, with the creation of two orchestras and a choral and operatic society under the auspices of Mr Albert Thomson, a reputed local musician.

Additional classes were laid on in the expanding fields of Accountancy, and Commercial Secretarial Skills. Languages were still a major offering and, despite tension in Europe, German classes were extremely popular. Students could even learn German shorthand. Esperanto and classes for English for Foreigners were also introduced. Courses leading to the National Certificate of Building Construction appeared for the first time in the 1936/37 curriculum.

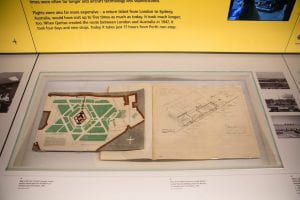

In 1937, the Technical Institute officially became a College for Further Education and plans for a new, larger building were developed. The proposed extension, which it was hoped would be begun in the College’s tenth year (1939) was budgeted at £122,442 with an additional £17,000 to be spent on furniture and fittings, apparatus and equipment and on the constructions of gardens and a roof garden. The new building was to be built on the rectangular plot on the south side of the former Vicarage gardens, in two distinct parts, with the main block lying alongside Warwick Road. Rectangular in shape, its west façade contained a huge window from the ground to the top of the building. The impressive entrance was situated in a rectangular tower and a 95-metre corridor would run the whole length of the building. It would be constructed in brown brick and Portland stone and set back from the road as the principal, Mr Trangmar “expressly requested that the green character of St Mary’s Road be preserved as far as possible.”

Students from the School of Art built a scale model following the plans prepared by the architects from Middlesex County Council. The “magnificence and magnitude” of the proposed building would “stand out in sharp contrast to the modest buildings which form the majority of St Mary’s Road.” The West Middlesex Gazette (WGM) further declared “it will be an architectural monument of which any borough could be proud.” However, world events would prevent the plans ever being executed.

In June 1937, a new sports ground opened, five-acres adjoining Pitshanger Park and Argyle Road. It had formerly been used by the Boys County School. The WGM noted that the facility was in surroundings “which create with astonishing success the deception of rurality.”

Ealing was growing rapidly as a borough. The area had seen big changes due to the move of industry to the Greater London region and while many of these opportunities required a technical education, in the eyes of the Middlesex County Times, Ealing “remained primarily a shopping centre”; that and its geographical location to London made it “an almost ideal situation for a school of retail selling.” The Department of Salesmanship for Retail Distribution, headed up by Mr Frank Keggins, was one of only four in the country. In harness with local shopkeepers providing practical experience, it offered prospective training in the psychology in modern salesmanship, as well as the importance of being “punctual, courteous, painstaking and exact”, and not treating your customer as a victim.

In 1938, the new prospectus was issued. It contained 82 pages of the more than 200 courses open to anyone in the Middlesex area at “very low fees.” The title page read “Ealing Technical College.” The establishment had been re-christened.

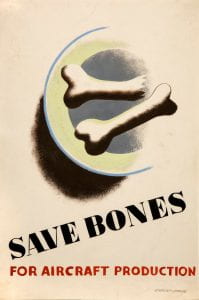

Part Three: The Second World War Years 1939-45

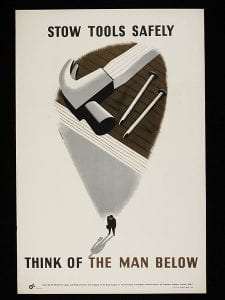

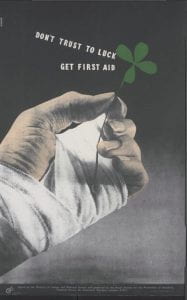

At the outbreak of war, the College premises were requisitioned by the Government but were soon returned with much encouragement to resume evening classes, as soon as the “necessary black-out provision was completed.” Eventually, the College also benefitted from being “adjacent to some of the most extensive and soundly constructed shelters in the county.”

The Technical College Junior School was relocated to Aylesbury and its young students were evacuated and billeted with local families.

In 1940, there was disappointment when a class on Current Events was not adequately attended. It was intended to include a weekly discussion on the war effort, news, economic factors and the many features of war-time conditions and “the very existence of this class…points to a fundamental difference between our democracy and Nazi Germany.” It was further speculated, “in Berlin there must be a strong potential for such classes; here the class is in session and you are encouraged to attend.”

During the war, with food rationing being a part of everyday life, the College supported local Rabbit, Poultry and even Pig Clubs as a way of members being able to obtain fresh meat. Recognising the stress that the population was contending with, the National Keep-Fit Movement was promoted by the government and a variety of classes were open to both sexes. In 1942, Russian was added to the Foreign Languages department.

In 1944, the college announced that, in preparation for peace-time, it would be reorganising its curriculum to provide degree courses in Arts, Commerce, Economics and Law, as well as classes on Current Events, Philosophy, Psychology and Sociology. The School of Art was adding Portrait Painting and Design for Fabric Printing, while the Technical Institute had was now offering Commercial Geography, Transport Horticulture and Poultry Keeping. Summer classes included “Make Do and Mend”, Wartime Cookery, Eurythmics and Folk Dancing.

In the penultimate year of the war, the 1944 Education Act was passed, with its emphasis on the provision of Adult Education. The original 1870 Act had introduced compulsory Primary Education, while Secondary Education became the focus of the 1902 Act. Finally, attention was turned to the adult population. As part of this initiative, Ealing College made introduced classes to young adults “whose education may have been interrupted by the war.”

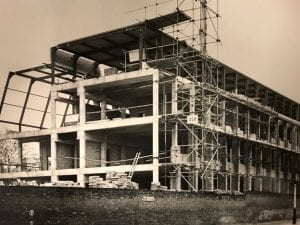

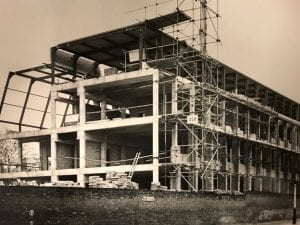

Part Four: Brand New Building 1949-52

By 1949, the old building was looking very dilapidated and was no longer fit for purpose.

A much larger new building was designed by Mr C. G. Stillman, the Middlesex County architect, who, during 32 years in local government service, built more schools and technical colleges than any other architect in the country. He believed it was important that school buildings “can be readily adapted to the needs of the future.” He predicted there would be an increase in television and film lessons and so classrooms needed walls that could be dismantled and reconstructed to “meet the classroom-theatre needs of the T.V era.”

The new building had “an imposing south front of Corinthian pillars”, according to the WGM.

It was completed in 1952, in time for accolade of the Ministry of Education recognising Ealing Technical College as being a Centre for Studies in Management.

Part Five: Growth in Size and Reputation 1953-69

At the end of 1953, Mr Trangmar, the Principal, retired after more than thirty years’ service. He had overseen the College’s growth from the days in which it was housed on the top floor of a Boys’ School, to a flourishing institution of more than 6,000 students, 57 full-time and over 200 part-time staff. He was succeeded by Dr O.G. Pickard.

By now, the College was the largest Art School and the best equipped Technical College in the country. A group of heads from German art schools had been over to visit the photographic centre, considered to be the best in Europe. The mid-fifties saw an explosion in the popularity of evening classes for all ages, and, according to the Middlesex County Times (MCT), “many housewives look upon these classes as an evening of recreation.”

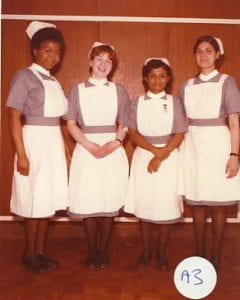

In 1957, Acton Hotel and Catering School left Acton Technical College (Woodlands Avenue, W3) to became part of the Ealing Technical College. With a reputation for being one of the top training schools in the country, its students went on to work in Paris, Geneva, top London restaurants, and many women went on to work for airlines of the day such as BOAC, TWA and BEA as cabin crew. The integration of so many additional students led to pressure for space, and as well as continuing in makeshift buildings in Acton, courses also took place in the County Horticultural Centre’s premises at Norwood Hall in Southall.

A four-storey East Wing was added to the College to house these additional students at a cost of £222,296. In 1962, a restaurant – the forerunner of today’s “Pillars” – was opened, where the public could eat lunch for 7s 6d (35p) cooked by the trainee chefs and served by the hospitality students, with alcoholic drinks also available.

A former NHEHS and Ealing School of Art student, 20-year-old Carolyn Turner won a sculpture competition organised by Middlesex County Council to decorate the new façade. Facing Warwick Road, the work, in ciment fondu, comprises both male and female figures, three single and a triple piece, 2.5m in height, and with an Egyptian influence. They symbolise catering, with cooks’ hats and catering equipment.

A former NHEHS and Ealing School of Art student, 20-year-old Carolyn Turner won a sculpture competition organised by Middlesex County Council to decorate the new façade. Facing Warwick Road, the work, in ciment fondu, comprises both male and female figures, three single and a triple piece, 2.5m in height, and with an Egyptian influence. They symbolise catering, with cooks’ hats and catering equipment.

In 1960, Ealing Youth Orchestra was formed, affiliated to the Music Department of Ealing Technical College.

The post-war baby-boomers were now approaching the age of 16, with “the bulge” leading to a growing demand for technical education. The first language laboratory in the country was installed in 1960, and an eye-catching article from the MTC in 1961 points out that the College’s sending its Secretarial students abroad for two or three months to work in foreign firms will provide invaluable contacts and knowledge “should Britain enter the Common Market.” The languages which were now being offered by the General Studies department included Russian, Chinese and Modern Greek.

In the summer of 1963, a further extension was approved costing nearly £183,000, to provide a new classroom and library block of five storeys at the rear of the hotel and catering school building, linked with the old structure by a two-storey bridge. Building work began in 1965 and was opened at Christmas 1966, by Mr Geronwy Roberts, the Joint Minister of State for Education and Science. Also, the adjacent Ealing Grammar School for Girls opened new premises at Queens Drive near North Acton station, and the College took over its former premises. In 1965, the College’s pioneering efforts in teaching business studies was rewarded when it was granted the right to establish a BA in Business Administration.

In the summer of 1963, a further extension was approved costing nearly £183,000, to provide a new classroom and library block of five storeys at the rear of the hotel and catering school building, linked with the old structure by a two-storey bridge. Building work began in 1965 and was opened at Christmas 1966, by Mr Geronwy Roberts, the Joint Minister of State for Education and Science. Also, the adjacent Ealing Grammar School for Girls opened new premises at Queens Drive near North Acton station, and the College took over its former premises. In 1965, the College’s pioneering efforts in teaching business studies was rewarded when it was granted the right to establish a BA in Business Administration.

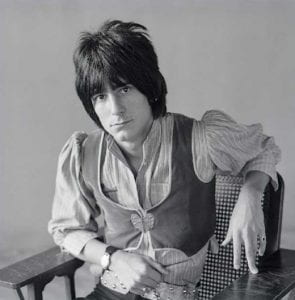

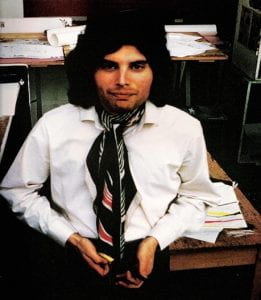

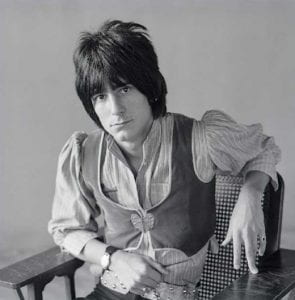

A miniature factory was set up in the fashion and textiles department, bringing the 60 students in contact with the processes of mass-produced fashion, aided by sewing machines, cutters and pressers. The College of Art was known for courses considered ‘revolutionary’ in the sixties, especially the two-year Ground Course run by Roy Ascott. Musicians Ronnie Wood and Pete Townsend both studied Graphic Art and Design in the early sixties, with Farrokh Bulsara, otherwise known as Freddie Mercury, graduating with the same diploma in 1969.

Pete Townsend

Ronnie Wood

Freddie Mercury

Despite these innovations and achievements, in 1966, Ealing Council had to protest when a White Paper proposing ten Polytechnics in the London and Home Counties area did not include Ealing Technical College in its plans.

Part Six: Towards a Polytechnic 1970-88

In the seventies, the Technical College went from strength to strength. In 1974, Mr Brian Price, a senior lecturer in the Hotel and Catering school, won “Chef of the Year” award, to the delight of his students.

In the seventies, the Technical College went from strength to strength. In 1974, Mr Brian Price, a senior lecturer in the Hotel and Catering school, won “Chef of the Year” award, to the delight of his students.

The following year, the Technical College was amalgamated with Thomas Huxley College, Acton (an institution training mature students to be teachers). This was a time when many teacher training colleges were closing nationwide. The resulting establishment was reorganised into a College of Higher Education and an entirely new governing board was appointed. At this time, there were 1,800 full-time and 3,400 part-time students.

In 1980, Ealing College Law Students became among the first in the country to be trained to use computers.

The business school grew to be one of the largest in the country with over 100 lecturers by 1981. Yet trouble arose in 1981 when the Tory Leader of the Council, John Wood, voted to cut the College’s annual budget by £200,000. This followed a prior cut the year before of £400,000. Sandra Jackson, a teacher at the College who represented it at the Further Education Sub-Committee meeting, made the point that the College already had to compete against universities and polytechnics, yet had met every target the borough had set it since the 1975 reorganisation.

In 1982, the College faced two types of cut – an Ealing Council-led cut with senior Tories wanting to axe four percent from budgets, and a Government-set cut, part of a nationwide axe. The cost-cutting threatened 33 lecturers’ jobs and affected 70 students already on fashion design diplomas, and the receptionists’ course, part of the Hotel and Catering School. Students marched on Ealing Town Hall in protest and staged ‘work-ins’ – sleeping overnight at the College premises.

In 1982, the College faced two types of cut – an Ealing Council-led cut with senior Tories wanting to axe four percent from budgets, and a Government-set cut, part of a nationwide axe. The cost-cutting threatened 33 lecturers’ jobs and affected 70 students already on fashion design diplomas, and the receptionists’ course, part of the Hotel and Catering School. Students marched on Ealing Town Hall in protest and staged ‘work-ins’ – sleeping overnight at the College premises.

In 1985, the newly opened Broadway Shopping Centre got a new neighbour when the College moved its Language School into 22,000 square feet of empty purpose-built office space in Grove House. Queen Elizabeth II paid a visit during Student Rag Week.

The College’s Polytechnic aspirations came a step closer in 1986 when plans were unveiled to merge the College with the West London Institute from September 1987. The College’s Academic Board approved the move on condition that all jobs were guaranteed, and that the new college be given Polytechnic status. However, this was interrupted by the 1988 Education Reform Act, which granted independence from local councils to more than 70 polytechnics and higher education colleges throughout the country. The Director of the day was Neil Merritt; he managed an annual budget of £15m, employed nearly 600 full-time and 400 part-time teachers, with 3,000 full-time or sandwich students and 600 part-time. Over 1,000 of the students were from overseas and altogether, they were contributing £7m to the local Ealing economy. There were four Faculties: Business & Law, Hospitality Studies, Humanities & Languages, and Information Studies.

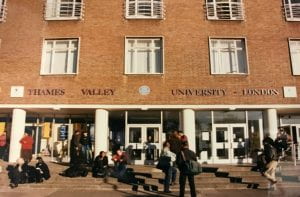

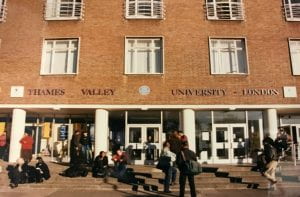

Part Seven: Thames Valley University 1991-2011

Finally, in July 1991, Ealing College of Higher Education merged with Thames Valley College of Higher Education, The London College of Music and Queen Charlotte’s College of Health Studies to become the Polytechnic of West London with Dr Mike Fitzgerald as vice-chancellor.

But life as a Polytechnic was short, as in 1992, university status was granted, and warranted another name change, this time to Thames Valley University (TVU). Student numbers increased rapidly, between 1994 and 1997 numbers grew from 16,000 to 28,000 students. In 1992, it topped the list for graduate employment, beating the University of Oxford.

In October 1996, Tony Blair, then Leader of the Opposition, opened the £8m Learning Resources Centre and praised the University for embracing new technology. Dr Fitzgerald introduced the New Learning Environment, which put students in control of their own learning, allowing more choice over the combination of subjects; instead of following set curriculum, they follow “pathways.” It also cut teaching hours and the number of modules from 8 to 6.

In 1998 Dr Fitzgerald resigned as Vice-Chancellor and in January 1999, a temporary Vice-Chancellor was appointed, Sir William Taylor, a man experienced in improving institutions. Discussions were held about possible mergers with, or certain departments being taken over by Kingston or Brunel, or even the further-flung Westminster or Reading but none of these came to pass.

Taylor successfully held the fort until a new permanent Vice Chancellor Kenneth Barker came on board. In February 2003, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) gave a clear endorsement to the University.

Lord Karan Bilimoria, Chancellor 2003-2011

In 2005 Barker oversaw the appointment of Lord Karan Bilimoria, the founder of Cobra Beer, as Chancellor. In 2007 Professor Peter John was appointed Vice-Chancellor and in 2009 the University was awarded the prestigious Queen’s Anniversary Prize for outstanding achievement and excellence in hospitality education in recognition of the quality of its teaching provision.

Part 8: University of West London 2011 – 2020

Laurence Geller, Chancellor since 2011

In 2011 the institution again changed name, this time to University of West London (UWL) and Laurence Geller, an alumnus of the Hospitality College, was appointed Chancellor. In the last decade UWL has invested more than £150 million pounds to the University’s facilities as part of a long-term strategy to continually improve the learning experience and social spaces and maintain UWL’s position as a leading modern University in London, with investment of more than £150million pounds. In 2013 UWL was granted planning permission to begin work on the Future Campus project. The same year a newly refurbished students’ union space and LCM Performance Centre opened.

Heartspace

In 2015 the St Mary’s Road campus underwent a multi-million pound transformation with the development of state-of-the-art facilities including a new social area, library, students’ union, auditorium, gym, restaurants and cafés, music and recording studios, and teaching spaces.

UWL purchased the Brentford site (Paragon) in 2016 and the following year saw the development of the Paragon Annex studios and the opening of a state-of-the-art nursing Simulation Centre at Reading. Also in 2017 the University achieved a Silver award in the Teaching Excellence Framework: Year two (TEF), recognising UWL’s strategic and innovative approach to curriculum, teaching excellence and focus upon a positive student experience.

LGCHT 70th Anniversary Gala Dinner (l-r): Prof. Peter John, UWL Vice-Chancellor, chef Andreas Antona and Laurence Geller CBE, Chancellor of UWL

In 2018 the London Gellar College of Hospitality and Tourism (LGCHT) celebrated 70 years of history through a series of commemorative events including a Gala Dinner at the Royal Garden Hotel.

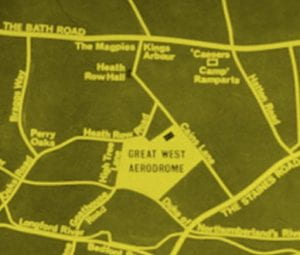

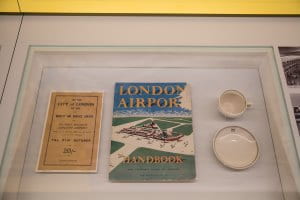

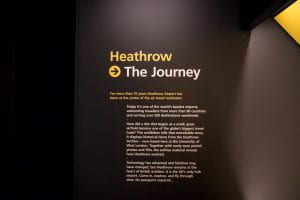

The same year UWL opened the West London Food Innovation Lab, a cutting-edge facility for new product development and innovation for food and drink businesses in the Greater London Area. The close business partnership between UWL and Heathrow Airport was strengthened through the opening of Heathrow: The Journey in April 2018, a permanent exhibition on the history of Heathrow Airport.

Westmont Enterprise Hub

The Westmont Enterprise Hub for Business Start-Ups was also created in 2018, designed as an ‘incubator’ offering entrepreneurs and start-ups the space and support to develop creative business ideas. Already the Hub has over 50 start-ups, 450+ members and connections to more than 500 businesses.

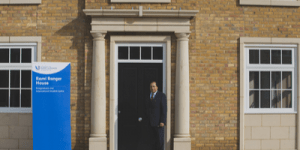

In 2019 Drama Studio London (DSL) became part of the UWL family. DSL is an Ealing institution well-known in the acting world with several famous alumni including Emily Watson and Forest Whitaker. Also in 2019, supported by a generous donation from Rami Ranger (Baron Ranger CBE) a dedicated postgraduate and international student centre was opened at the Ealing campus. Rami Ranger House is a supportive and collaborative learning space for students undertaking postgraduate studies.

Baron Rami-Ranger outside Rami-Ranger House

UWL’s eight academic schools and colleges offer a wide range of options for postgraduate study including Masters, Postgraduate Diplomas and PhD courses. Currently 700 of UWL’s 12,000 students are postgraduates with recruitment increasing year on year. A state of the art Sports and Fitness Centre opened in November 2019 at the St Mary’s Road campus as part of the University’s ongoing investment in improving facilities and promote health and wellbeing across the community. UWL has also partnered with Ealing Council and Hounslow Council to build a brand new sports and leisure facility in Gunnersbury Park. The centre, costing approximately £14m, will be accessible to UWL students and is due to open in 2020.

In recent years UWL has also developed a strong reputation in applied research, providing insight and solutions to real-world problems and follows a Research Excellence Framework (REF) strategy with a vision to be ranked within the top 100 universities in REF 2021. The Graduate School exists for doctoral students and the ExPERT Academy facilitates the University Pedagogic Research & Scholarship Community (PRSC). In 2015 The University launched New Vistas, a publication which features research and scholarly analysis on policy and practice in higher education. The journal invites contributions from UWL academics and doctoral students, as well as external authors. The journal’s aim is to showcase research in a modern university as it impacts on society, industry, and services. UWL also hosts several important research centres including the Cybersecurity and Criminology Centre and the Richard Wells Research Centre which focuses in improving patient safety.

All of these recent additions and developments indicate that UWL is thriving, with a reputation for being “cool”; it is known as “The Career University” and the “top modern” university in London[1]. Currently UWL enjoys a high employment rate of 98% of UWL graduates who start their careers or carry on their studies within six months of graduating[2].

Professor Peter John is credited with the transformation of the institution into the highly successful one it is today and was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the Queen’s 2020 New Year honours list for his outstanding work and service to higher education. Now one of the top ten modern universities in the UK, it is a flagship for the benefits of widening participation, social inclusion, and meritocracy.[3]

[1] UWL is the top modern university* in London for overall satisfaction, according to the National Student Survey 2019 (Modern = granted university status in, or after, 1992.).

[2] (HESA employment indicator 2018 on graduates who say they are working or studying (or both) six months after completing their studies).

[3] https://www.uwl.ac.uk/news-events/news/uwl-vice-chancellor-professor-peter-john-awarded-cbe-new-year-honours-list

Layers of London: https://www.layersoflondon.org/

UWL: www.uwl.ac.uk